Coming up in the near future we’ll be using this blog to discuss chess engine functions in ChessBase 11, Fritz12, Rybka4, etc. But before we jump into detailed explanations of these functions, it’s a good idea to take the time to review some of the basic concepts and visual displays relating to chessplaying programs in ChessBase software.

Whether you’re running a chess playing/analysis program (a.k.a. an “engine”) inside the ChessBase database program or in an engine’s own native interface (that is, within Fritz, Rybka, etc.), you’ll see similar displays for what the engine is “thinking” in a given position. This display is called the “engine pane”, and it’s not very different between ChessBase and Fritz/Rybka/etc.

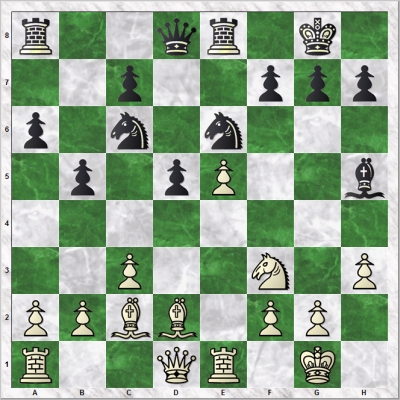

Let’s fire up the engine to analyze a position. We’ll use the final position of the fourth game of the 1978 World Championship match between Karpov and Korchnoi. Karpov as White played 19.Bd2 and the players agreed to a draw:

So we’ll start Fritz12 and see what Fritz thinks of the position. I took a screen capture just over a minute into the search, and this is what the engine pane looked like:

We’re not going to discuss every aspect of the engine pane in detail in this post, just the basics you’ll need to understand what the engine is telling you.

Aside from the positional evaluation itself, the most important piece of information is the “Depth” value. Quite simply, this tells you how far ahead the engine is looking. It’s crucial to understand that the depth value is given in plies. A “ply” is a half move – in other words, a move for one player. You’ll recall that Black is to move in the current position (and it would be Black’s 19th move); while the engine is evaluating Black’s moves in this position, it is doing a one-ply search. When it finishes (and records the best move for Black) it starts analyzing and evaluating all of White’s replies to each of Black’s possible 19th moves. So as it is analyzing White’s possibilities at move 20, it’s doing a two-ply search (and Fritz would display a “Depth” value of “2”). When Fritz finishes that ply and begins evaluating all of Black’s move 20 replies to White’s moves, it’s performing a three-ply search (and the “Depth” value would be “3”).

Present-day commercial chess engines analyze incredibly quickly; in USCFSales’ latest YouTube video, I demonstrate how Fritz12 performs a seven-ply search in just one second. That’s amazingly fast (and especially so to those of us who were using chess software twenty years ago, when a search to a depth of seven to nine plies took four or five minutes on a then state of the art computer possessing a 386 processor). When you first start an analysis engine in ChessBase or Fritz/Rybka, you can usually expect to see a double-digit search depth value within a couple of seconds.

Notice, though, that the value after “Depth=” in the illustration above consists of two numbers separated by a slash. The number to the left of the slash is the regular depth value, in which Fritz is looking 19 plies ahead. The number to the right of the slash is called a “selective search” value, in which a chess engine is able to look far more deeply in certain forcing variations which contain tactics, exchanges, checks, etc. In the present position, Fritz can look a whopping 41 plies ahead in these forcing or tactical lines.

In the next box to the right, we see a move along with two additional values within parentheses. The move displayed is what Fritz is currently considering – right now it’s evaluating the consequences of 19…h6 (to a depth of 19 plies, as we saw earlier). The second number within the parentheses indicates the total number of possible moves in the current position – in the board position shows above, Black has 38 possible moves. A chess engine will create a “sort order” of possible moves based on their likelihood of achieving a promising result (and it will change the ranking of these moves as the search depth increases). At present, Fritz considers 19…h6 to be the second-best move of the 38 moves possible, which is why the number to the left of the slash is a “2”.

Watching that part of the display allows you to get a better idea of how far the chess engine has progressed in its search. Within that 19th ply, Fritz has completely evaluated one of the 38 possible moves and is now analyzing the possible consequences of the second of the 38 possible moves.

The next value to the right shows how fast Fritz is analyzing. The number is given in kilonodes per second (kN/s). A “node” is simply a board position; therefore a “kilonode” represents a thousand positions. We can see that Fritz is currently evaluating at a speed of 2135 kilonodes per second – 2,135 thousand positions per second. In other words, Fritz is evaluating more than two million positions every second.

At this point, I will bring up an important point about computer chess engines: the engine will always give you the best move/variation it finds within the time you give it to think. The corollary to this is: the more time you allow a chess engine to think, the better the move/variation you receive in return.

That brings us to the main display – the large box of the analysis pane. This displays the best variation the chess engine has found up to this point, assuming best play for both sides. Fritz is currently displaying a variation beginning with 19…Nc5, which means that at present Fritz thinks that 19…Nc5 is the best move for Black. This “best” move may change as Fritz’s search depth increases and it looks farther ahead to evaluate more positions and more consequences of Black’s 38 candidate moves.

We also see some additional information on a second line. The first information is Fritz’s analysis of the displayed variation – after that entire variation (through 27…b4) is played out, the position will be about even (hence the equal sign; you’ll see the standard Informant evaluation symbols used here), while the numerical evaluation stands at 0.18, which means that White will have the better position by eighteen one-hundredths of a pawn.

The numerical evaluation is always given in pawn values (meaning that a value of 1.00 indicates one pawn). A positive value means that the position is better for White while negative numbers mean that a position favors Black. It’s also useful to note here that chess engines don’t only consider material when making their evaluations – they also take positional considerations (space, pawn structures, etc.) into account as well.

The “Depth” entry after the variation isn’t referring to the current status of the search; it instead refers to the depth status at the time the engine decided on the displayed variation as being best play for both sides; hence we see that Fritz had achieved a regular search depth of 19 plies and a selective search depth of 41 plies at the time the current variation was posted to the screen. With the next value to the right, we see that Fritz had been evaluating for one minute and eighteen seconds when it decided on the displayed variation, and had evaluated 168 mega nodes (168,000,000 individual positions) to reach that decision.

The variation displayed at the bottom of the engine pane displays the line of play which the engine is currently considering.

As stated before, you will likely see a chess engine “change its mind” as it looks more deeply into a position’s possibilities, and the deeper it searches, the better the analysis you’ll receive in return. Here’s what Fritz’s analysis of the above position looks like after the engine was evaluating positions for over one and three-quarters hours:

Fritz is presently looking twenty-five plies deep. It still thinks Black’s best move is 19…Nc5 but the subsequent moves have changed. The overall evaluation has also changed (0.02 – dead even for all intents and purposes). Catch this: Fritz has analyzed over thirteen billion individual board positions to make its decision on the best line of play.

So we’ve now learned that Karpov and Korchnoi were justified in agreeing to a draw in this position.

Now that we’ve reviewed what Fritz12, Rybka4, and other chess engines are telling us in the engine analysis pane, we can move ahead to other functions of this pane in these playing programs (as well as in ChessBase 11). Until we do…

Have fun! – Steve Lopez

Chessplayers who have purchased their ChessBase brand software from USCFSales can receive free technical support and advice on their purchases straight from me; just shoot me an e-mail (steve@uscfsales.com), but please remember to include the USCFSales order number from your ChessBase software purchase. – Steve

Copyright 2011, Steven A. Lopez. All rights reserved.

Pingback: Making your chess analysis engine stronger | USCFSales

In the analysis window, some lines are sometimes colored red or green, in addition to the normal black. What do theses colors signify?

IIRC, it represents a “fail low” or “fail high”, meaning that the engine has just discovered a line of play which changes the evaluation by 1.00 or more.